Bite-sized Pieces of the Feasibility Report - Pt 1

We are launching a newsletter campaign to highlight small sections of the upcoming feasibility report! Every week after we email our subscribers, we’ll add the content here for anyone who missed it!

Watch for Part 2!

If you’d like to get the newsletter, scroll to the bottom of the page to subscribe!

“Value” is more than dollars and cents; it’s the social cohesion, opportunity for belonging and ability to share knowledge in a community.

The mission of the Athabasca Grown project is to strengthen the local food system, inspire growers, and foster community relationships.

We envisioned this mission on the values of resilience, accessibility, and sustainability.

A Different Kind of ROI

Return on Investment (ROI) is a widely used profitability measurement that evaluates the performance of an investment. This traditional approach would treat a deep-winter greenhouse as a simple cost-benefit equation: high initial capital costs and operating expenses against revenue from selling winter produce. It tallies direct sales of lettuce and tomatoes, but ignores the high-value benefits achieved elsewhere in the community.

Social Return on Investment (SROI) is a principles-based method for measuring extra-financial value (such as environmental or social values). It requires a different calculation and a fundamental shift in the definition of "profit."

It is the practical expression of a circular economy, where the demand for a winter cuke or tomato flows directly into local economic multipliers, improved human health, and community well-being.

SROI includes investment dollars but also volunteer hours and local talent. It values the contribution of knowledge, understanding and wisdom. It takes into account concepts such as resilience, self-confidence, self-realization, control of local food security, local supply/demand and local employment.

It’s the difference between buying lettuce from California and Mexico, or learning how to grow them yourself in the dead of winter. The deep winter greenhouse becomes a tangible learning centre, budgeted as an educational infrastructure investment akin to a library. The metric isn’t how many kilograms of food are sold, but how many engaged citizens of all ages gain the capacity to participate in regenerative agricultural growing principles.

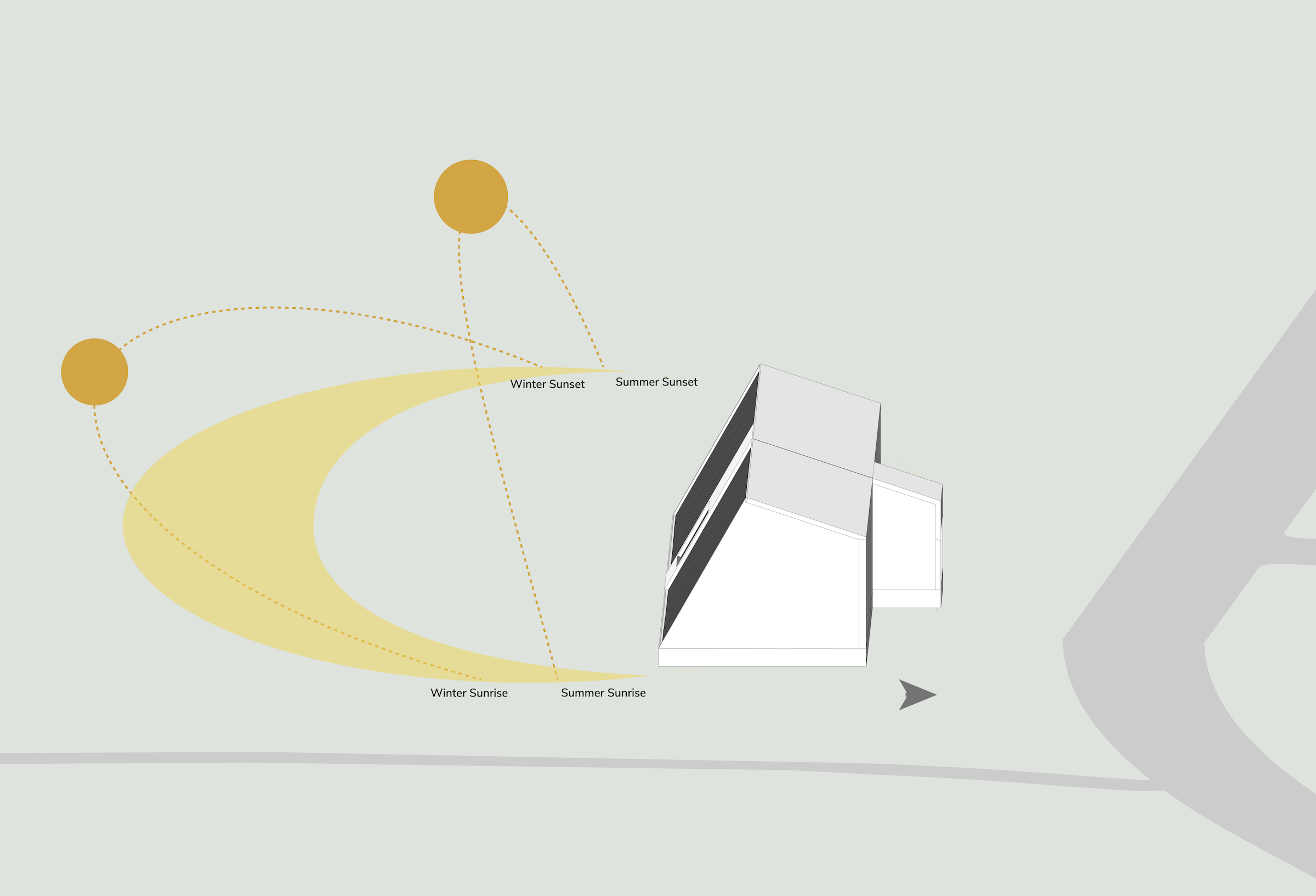

It is essential that the south-facing side of the greenhouse is not shaded, allowing the winter sun to reach the plants through the optimally angled glass or polycarbonate panels.

Location, Location, Location

Several local properties have been explored for the Athabasca Grown Greenhouse, each offering distinct advantages and challenges. Critical requirements include a sufficient power supply for running supplemental lighting, heating, and ventilation systems, while adequate water access is required for irrigation and humidity management. Stable internet connectivity is increasingly important for monitoring environmental controls, managing remote sensors, and enabling educational or commercial livestreaming opportunities.

Shading from nearby trees or buildings reduces the effectiveness of passive solar design or impedes potential photovoltaic (PV) integration. High winds demand stronger framing and contribute to climate variability, while uneven ground can significantly increase site preparation costs. Overhead power lines may limit building height and solar panel placement, and flooding risks or a high water table can compromise long-term stability. Local bylaws and access to services must be confirmed early to avoid setbacks. The site must be sufficiently sized to accommodate the greenhouse, with space for parking, potential growing areas on the surrounding grounds, and future expansion.

The ideal location would build cooperation with nearby community assets. Near the Multiplex provides visibility and ease of direct sales. Adjacent to EPC provides student engagement and learning opportunities. Being close to a seniors’ residence may facilitate volunteer participation. Proximity to an existing commercial kitchen could support value-added processing and small business incubation.

Learn more about siting and orientation of passive solar buildings here: www.greenspec.co.uk/building-design/solar-siting-orientation

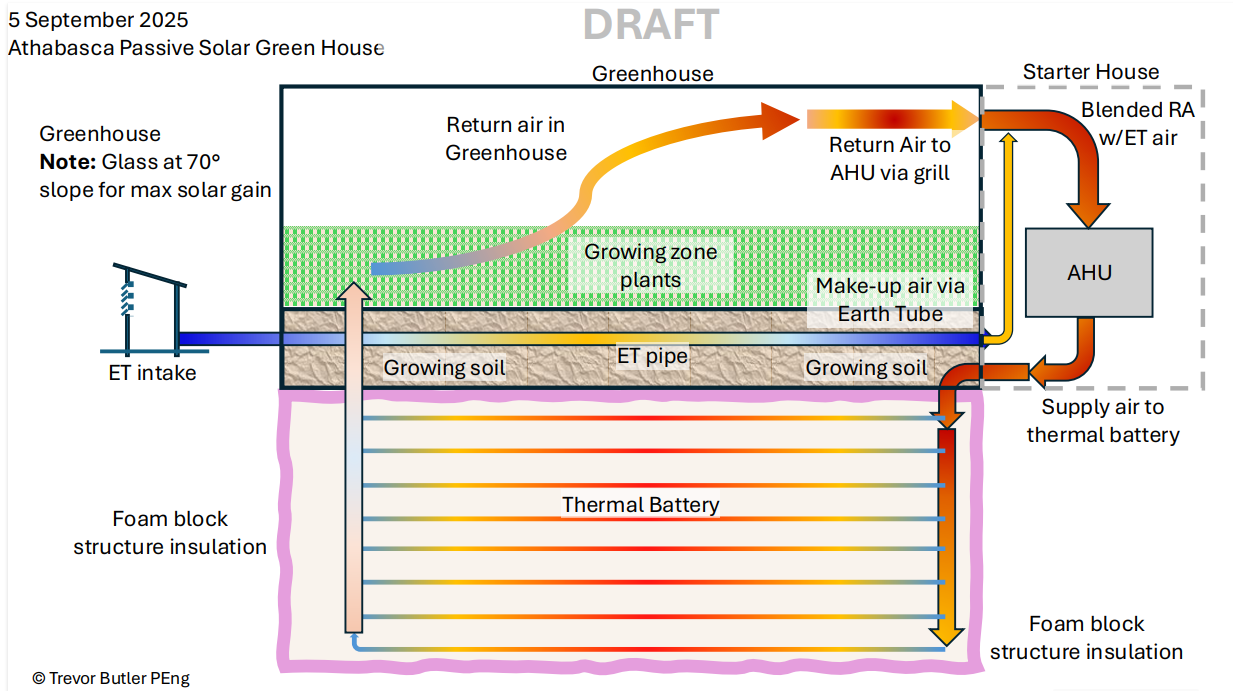

An example of a climate battery system. The Athabasca Grown Community Greenhouse will use a similar system.

Climate Battery Technology

A climate battery uses the earth, or another subsurface material, as a thermal reservoir, enabling a winter greenhouse to operate primarily on heat gain from the sun to maintain a stable growing temperature, with reduced additional heating.

This is accomplished through a four-step cycle: collecting, circulating, transferring, and then reversing the process.

Heat Collection: During sunny periods, the greenhouse often generates more heat than needed. Instead of venting the excess hot air outside, low-power fans pull this warm air from the top of the greenhouse.

Underground Piping: The warm air is then circulated through a network of perforated pipes buried beneath the greenhouse floor.

Heat Transfer and Storage: As the warm air travels through cooler earth, it transfers its heat to the surrounding soil. The soil acts as a "thermal battery," storing this heat. Any moisture in the air may also condense in the pipes, releasing latent heat and helping to dehumidify the greenhouse.

Heat Retrieval: When the greenhouse needs heating, the same fans (or a separate set) reverse the process, drawing heat from the stored thermal energy in the soil, and returning warmed air to the greenhouse.

Benefits of Climate Batteries

While some use a climate battery to achieve tropical growing goals, we are focused on producing local varieties, only beyond the natural season. Even with a climate battery, additional heating and lighting will be needed to maintain growing conditions on the darkest, coldest Alberta winter days.

Lower Operating Costs: Dramatically cuts heating expenses (by up to two-thirds) compared to propane or electric heaters by using the sun's free energy.

Temperature & Humidity Regulation: Creates a stable, even environment, preventing extreme heat spikes in summer and chilly lows in winter, reducing plant stress and improving photosynthesis.

Soil Conditions: Keeps the root zone warmer and more stable.

Self-Reliance: Creates a more self-sufficient greenhouse, relying less on external energy sources and fossil fuels.

Reduced Emissions: The reduction in fuel consumption translates to reduced environmental impact.

Learn More

wolpinenterprises.ca/farm-supplies/climate-battery/

ceresgs.com/10-dos-and-donts-for-designing-a-ground-to-air-heat-transfer-system/

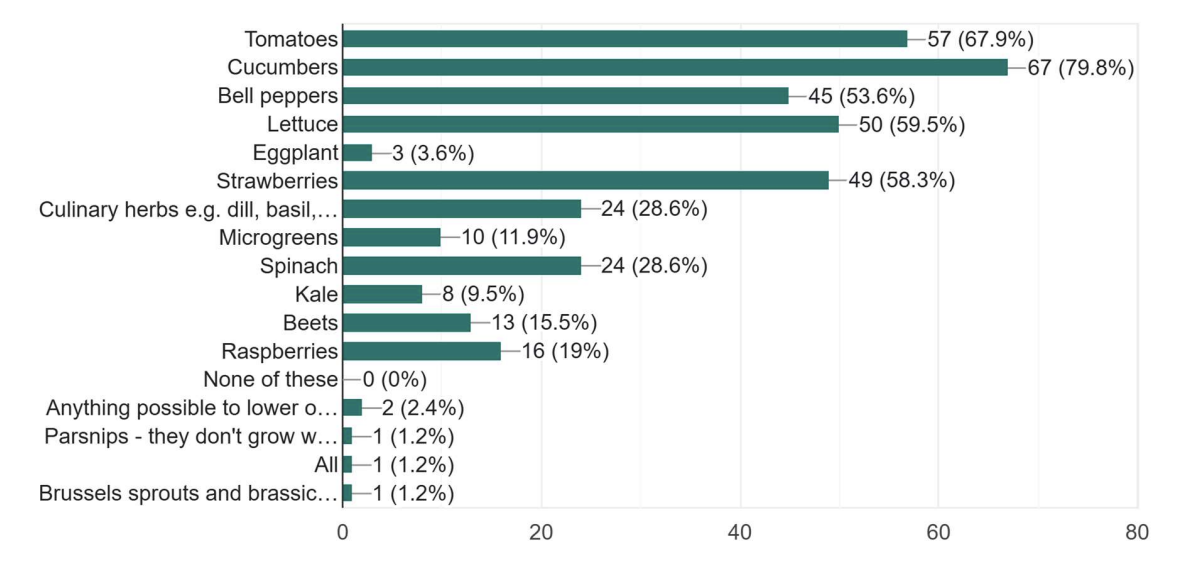

From our community survey: “Which of the following common greenhouse crops would you most like to see produced in Athabasca County?”

The top 5 were cucumbers, tomatoes, lettuce, strawberries and bell peppers.

What to grow, what to grow?

Before the leafy greens and trellised tomatoes show their little green shoots, several considerations are being weighed.

Selecting crops for the Athabasca Community Greenhouse requires balancing climate, space, labour, productivity, and market needs. These factors influence greenhouse design, operational requirements, and potential profitability.

Crops vary in tolerance to low light, cold, and poor ventilation, with leafy greens generally more forgiving than fruiting crops like tomatoes, peppers, and cucumbers.

Different crops require different horizontal and vertical spaces. Lettuce needs under 1 ft² per plant, while cucumbers and tomatoes require 3–5 ft² with trellising. Crop cycle length affects how often areas need replanting; fast-turnover crops like leaf lettuce and spinach allow multiple harvests per season, while long-cycle crops such as peppers or strawberries require sustained care.

Prices must be cost-competitive. Customers will only pay what they pay now, even if the locally produced food is of higher quality or nutritional value.

Initially, the crops to be grown include:

Leafy greens such as spinach and lettuce;

Herbs like dill, basil, and parsley;

Vegetables and fruit such as cucumbers, tomatoes and strawberries.

Civic Agriculture in Action

Civic agriculture refers to community-based agricultural practices aimed at reconnecting food production with local communities. Coined by Thomas Lyson, the term emphasizes the importance of local food systems in promoting social sustainability and economic development.

With an emphasis on the current state of food production, distribution, and consumption, the Connect for Food workshop, held in Athabasca in January, generated valuable insights into how we can shift towards a more sustainable and resilient food economy in our own region.

To strengthen the food system, it is crucial to support small-scale producers, build infrastructure to facilitate local food production and distribution, and promote seasonal eating. Greater transparency in food sourcing and increased consumer education on food business practices will empower consumers to shape a food economy that aligns with their values.

Changes discussed included:

Building stronger community connections between growers and consumers;

Educating consumers, particularly young people, about food holistically is seen as key to instilling healthier food habits. Refocusing on food as an experience, rather than a task, will support appreciation of the work that goes into food production and encourage mindful eating;

Policy reforms, creating accessible financing options for food businesses, and incentivizing local food production.

Fresh Local Produce in Midwinter

Why is the proposal for a three-season (fall, winter, spring), deep-winter solar greenhouse?

Interviews and surveys identified a clear seasonal gap in local produce from October to March, which presents a good income opportunity for the project.

The building will combine passive solar design with modern environmental control systems to minimize energy inputs while maintaining optimal growing conditions. The structure prioritizes low embodied carbon, using as much wood as possible in its framing, and employs efficient heat storage, lighting, and ventilation systems to ensure steady production even through short, cold days. The greenhouse will serve as a demonstration of sustainable, locally appropriate technology that balances energy efficiency, material responsibility, and year-round food security.

Potential crops that grow well in a greenhouse setting, provide good nutrition and taste, and might find a profitable winter market include leafy greens such as spinach and certain lettuces; herbs like dill, cilantro, parsley, and basil; and fruits and vegetables like cucumbers, tomatoes, and strawberries.

To stay updated with the Athabasca Grown project, subscribe to our Newsletter below.